Aside from blatant disregard for people of color’s health as seen in Flint, Michigan, environmental injustice can also be seen on a smaller scale. Less obvious health hazards can quickly add up and severely jeopardize the health of our most vulnerable members of society. Some examples include a lack of nature in poor neighborhoods to decreased access to nutritional foods in communities of color to allowing oil fracking near low-income schools. These three examples tell a story all too familiar. Imagine a person only has access to the fast foods available and is later diagnosed with obesity. Many will say they can simply work out to become healthier. However, their neighborhood is unsafe to exercise outside. And why would they want to go outside anyways? The air is too polluted from the nearby fracking. They were diagnosed with asthma from exposure at a young age. In addition, the lack of nature and beauty in their area causes them to stay inside, exacerbating their obesity and causing a decline in their mental health. When all these seemingly negligible factors are combined, which they more often than not are, years can be taken away from a person’s life.

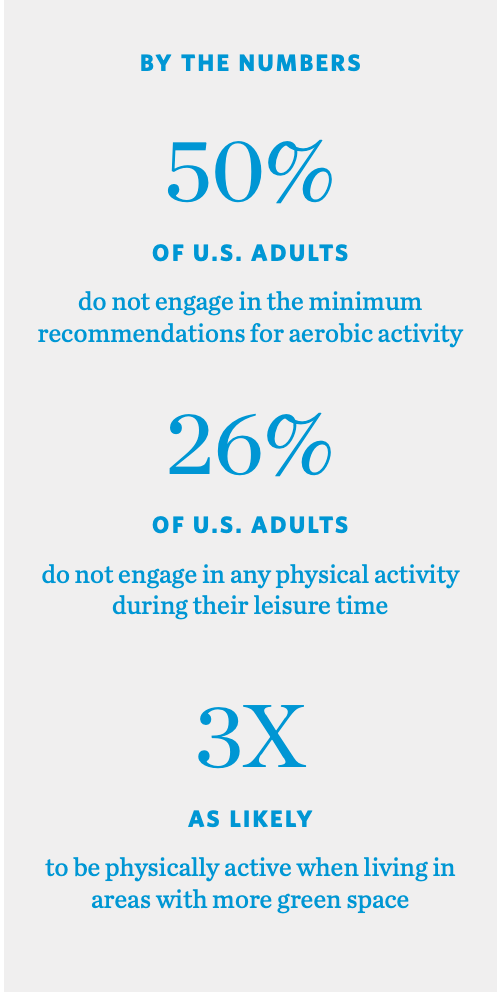

To expand on one of my previous examples, one often overlooked inequality is the lack of nature within communities with high minority populations. Left without trees, which filter out air pollutants, and “green spaces” like parks, the residents face higher concentrations of air pollution, which cause respiratory illnesses like asthma. In fact, a 2010 study found that trees prevented 670,000 cases of acute respiratory symptoms in the US. Nature has also been seen to have positive mental effects: reducing stress and providing therapeutic benefits to people living with mental disorders. Studies show that exposure to nature speeds up recovery time for hospitalized patients and motivates healthy behaviors such as exercise.

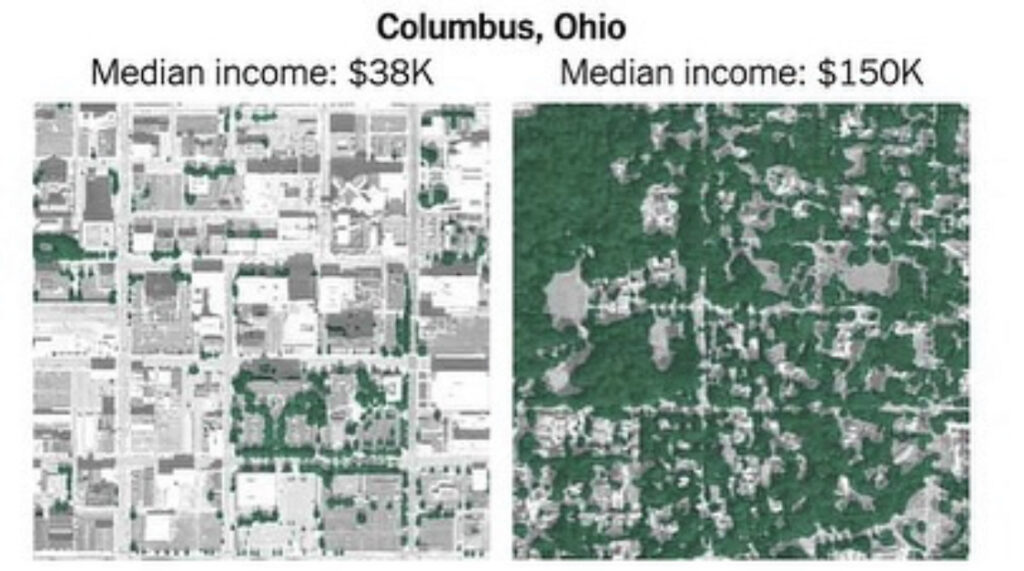

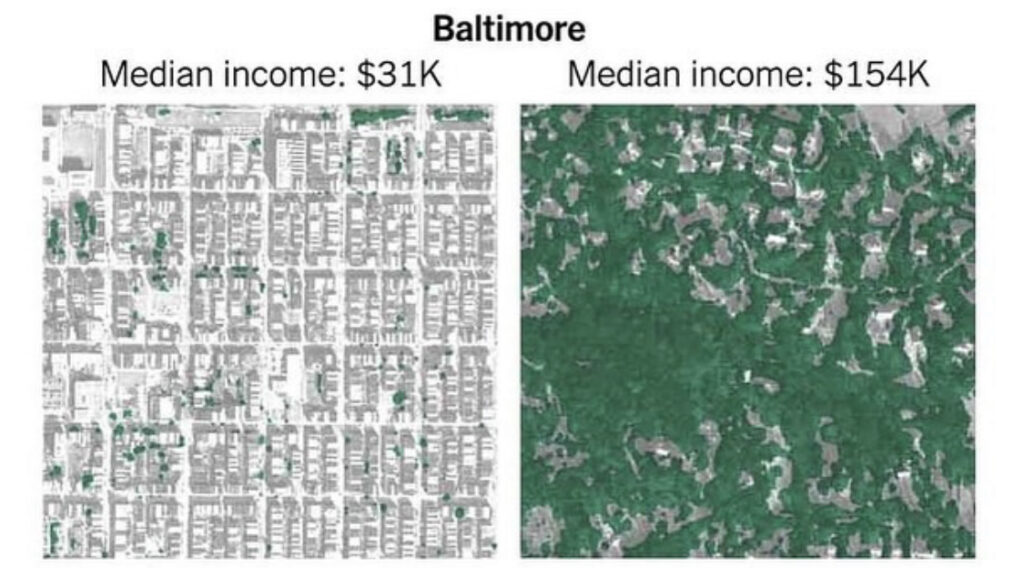

However, too often poor and POC communities have less dense tree coverage than their white counterparts.

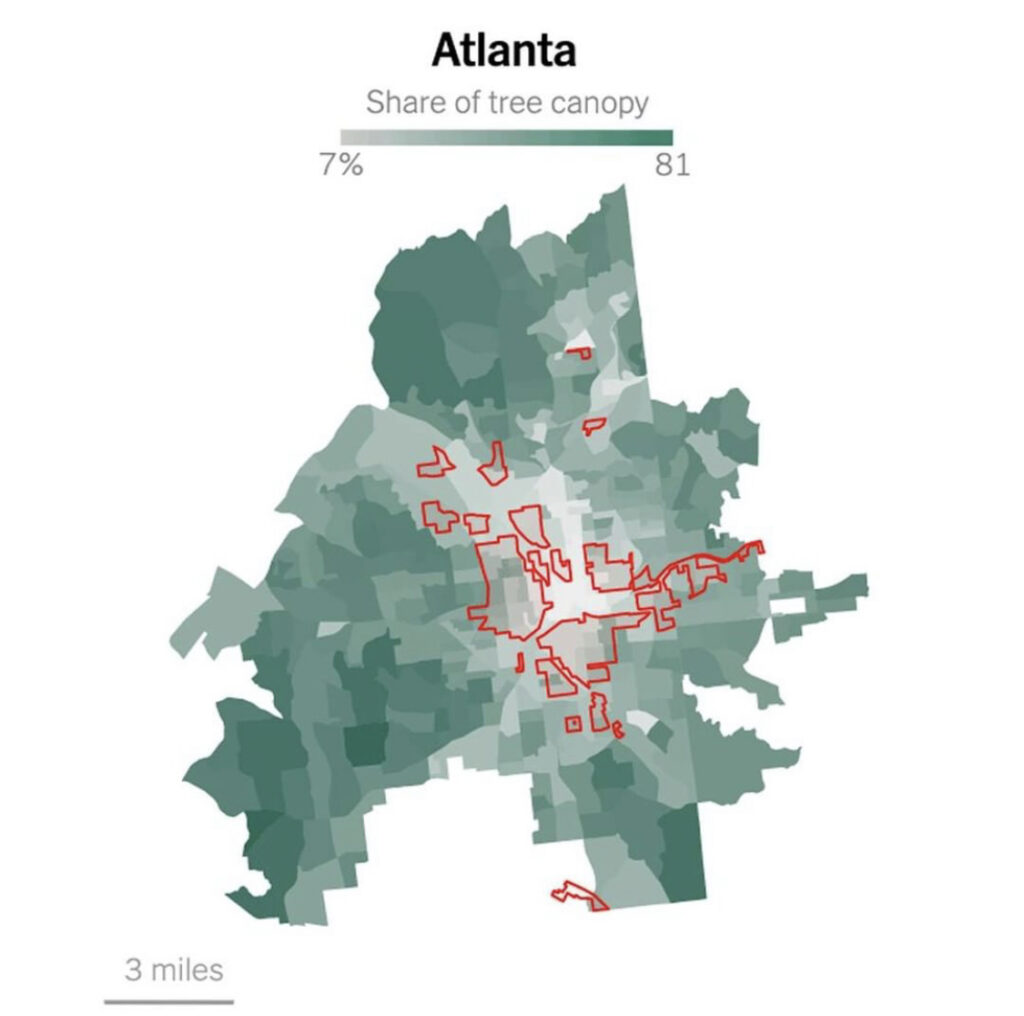

In the images above, a map illustrates how tree cover in cities is too often based on income and race, where trees are sparse in low-income neighborhoods. Another graph below shows how the effects of redlining, a form of segregating neighborhoods, can still be seen today in the form of tree inequity.

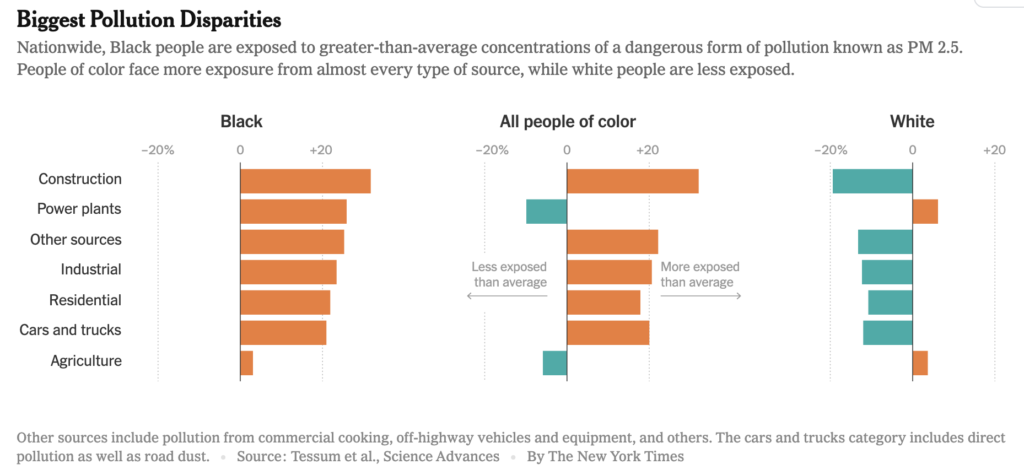

But how is this constituted as a racial issue? Certainly not all city planners are hatching a plot to poison people of color? You’re right, that idea would be absurd. But even though a racist city planner isn’t consciously withholding amenities from communities of color, the fact is that minorities are still exposed to more pollutants, in almost every category from agriculture to residential to transportation, than their white counterparts. Whether intentional or not, the disregard for people of color’s wellbeing and little to no remediation of these inequalities furthers the idea that leaders consider minorities’ health unimportant. In my next blog post, I will dive deeper into why this environmental racism exists today and the steps being taken to fix these problems.

Sources and More Information

Since When Have Trees Existed For Only Rich Americans?

People of Color Breathe More Hazardous Air. The Sources Are Everywhere

Trees clean the air and prevent respiratory illnessOil and Gas Extraction and the Effects on Public Schools in Los Angeles .