As discussed in this month’s previous blog entry, environmental justice is a movement that seeks to ensure that decisions related to environmental policy and implementation include the groups and community that are most affected by those policies.

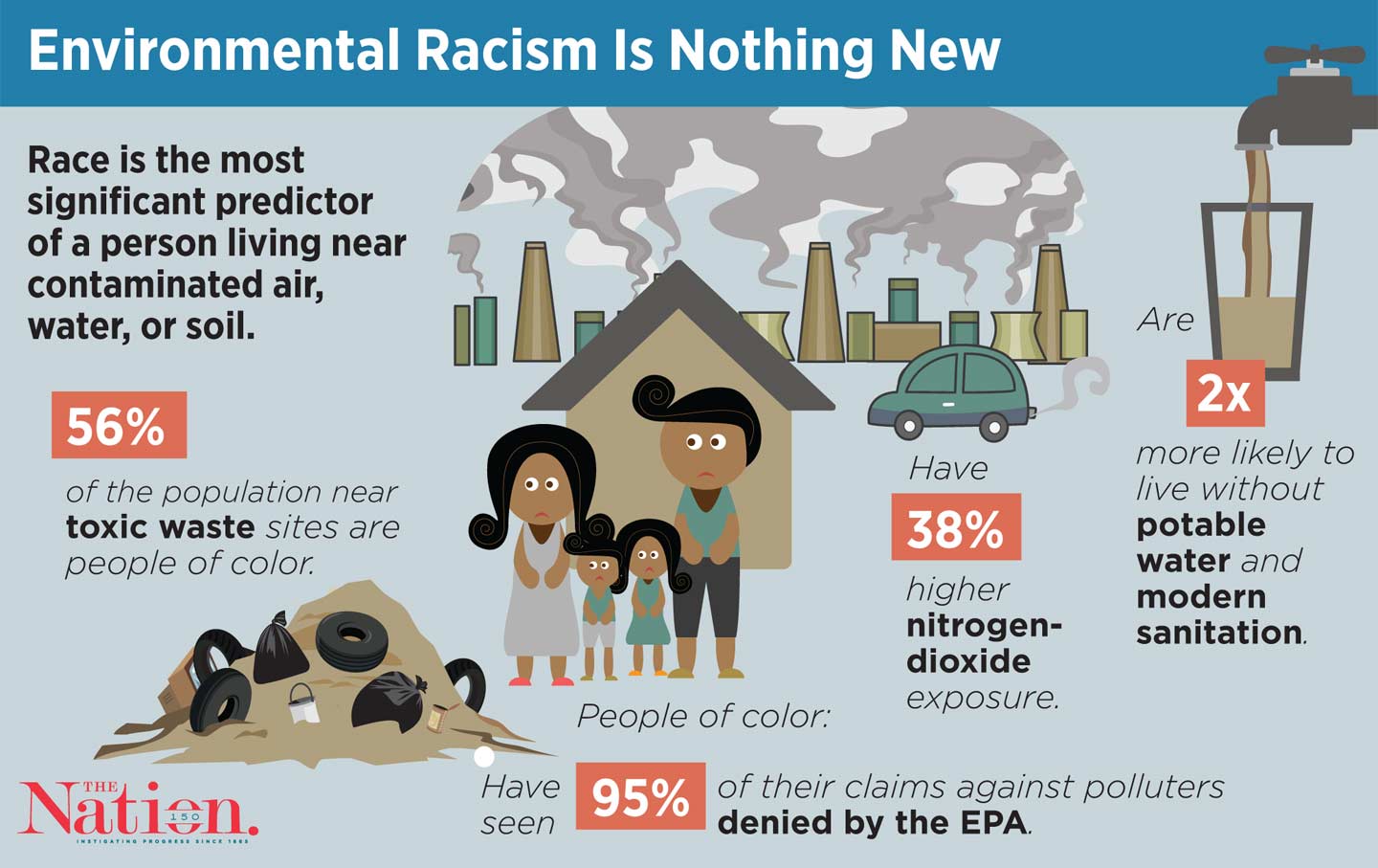

Environmental justice encompasses the equal distribution of environmental hazards as well as the equal distribution of environmental resources. Environmental racism refers to communities comprised mostly of people of color bearing a disproportionate, unequal burden of environmental hazards. The term also describes situations in which these communities lack many of the environmental resources, such as green spaces, safe buildings and housing, and clean water, that other communities enjoy.

While many generations of people of color have felt that environmental racism is a systemic, widespread problem, decades of empirical research proves that environmental racism is an extensive problem that exists in the United States, repeating itself throughout time and geographic space.

Beginning in 1983, a study published by Robert Bullard, credited as the “father” of environmental justice, found that solid waste sites in the Houston, TX area were not scattered randomly across the city. Instead, Bullard found that these waste sites were likely to be found in African American neighborhoods and schools. Other studies quickly followed, including a 1983 study released by the United States Government Accounting Office and a 1987 study undertaken by the United Church of Christ. Findings from these two studies reinforced what communities of color have known for years. Some of the most noteworthy discoveries were:

- A 1983 study by the U.S. Congress’s General Accounting Office found that in eight southeastern states, 75% of the hazardous waste landfill sites were in low-income communities of color.

- A United Church of Christ found that race was the most critical factor in determining where toxic waste facilities were sited in the United States, more than income.

Throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, study after study showed the pervasive existence of environmental racism even when controlling for variables such as income. A 20 year comparative study by Bullard published in 2007—more than 30 years after his first ground breaking study–found “race to be more important than socioeconomic status in predicting the location of the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities.”

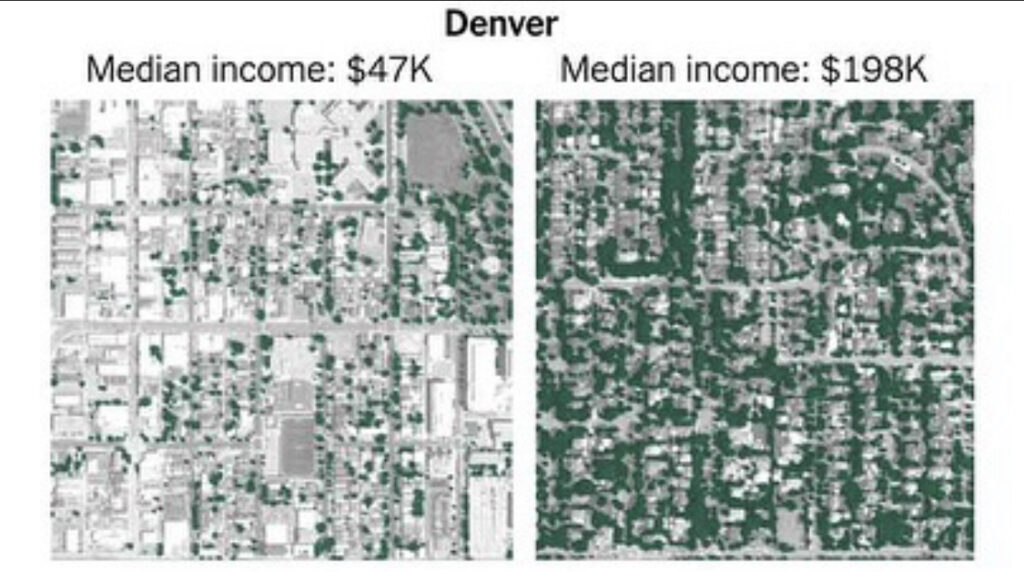

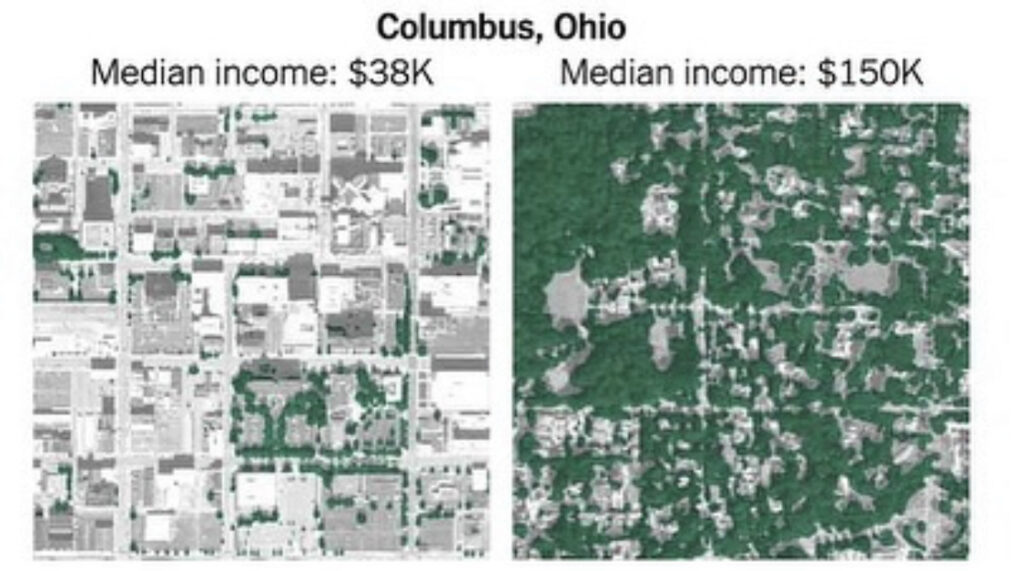

While the proximity of communities of color to hazardous environmental elements constitutes a big focus of the environmental justice movement, environmental justice and environmental racism also encompass problems associated with the lack of resources enjoyed by other communities—markets with an abundance of fresh fruits and vegetables; plentiful outdoor space for exercise and recreation; streets lined with trees and plants to reduce the temperature of neighborhoods during the summer and reduce carbon dioxide and soil erosion throughout the year.

A twenty-year comparative study led by sociologist Robert Bullard found that African American children are five times more likely to have lead poisoning (the leading environmental health threat for children) than their Caucasian counterparts.

- According to a 2014 study, minority neighborhoods have far less access to green spaces than communities that are primarily White. Some might argue that Black people could simply move or add more greenery to their neighborhoods. However, some Black people cannot afford to live in greener neighborhoods. And if Black communities add more green space, housing prices often increase, which leads to gentrification.

Source: “Since When Have Trees Existed Only for the Rich?”

- Two studies from 2009 and 2012 found that minority neighborhoods are more likely to have access to unhealthy food options and less likely to have access to healthy food options. More fast food and less produce can lead to obesity, which is linked to risks like heart disease, strokes, high blood pressure, some types of cancer, diabetes and more.

- A case study in Detroit found that people in the poorest Black communities live an average of 1.1 miles farther from a supermarket than those living in the poorest White neighborhoods. Having less access to supermarkets can make it harder to find nutrient-dense foods.